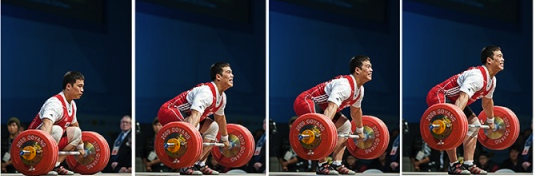

Presenting The 5 Phases of the Snatch/Clean in Weightlifting.

In a previous article about key positions, I have mentioned that positioning is important in weightlifting. It allows for maximum utilisation of the body's leverages to produce force and transfer it to the movement of the barbell. However, solely looking at the positions leaves out the movements that allow these positions to be adopted and misses out on what actually causes the lift to fail. Thus, understanding the actual movement of the levers to achieve one position to another is what the phases of the lift are about. By analysing not only the position and possible finding faults with it, looking at the phase that preceeds it will tell the story for the faults in that position. So combining both is what you should have as your arsenal in technique analysis. So let's take a look at the different phases and what's commonly mentioned about them and the common mistakes.

1. The First Pull

Image from Rob Macklem.

Image from Rob Macklem.

This starts with the start position where the barbell is about to be lifted off the ground until the barbell reaches knee level. This is done by using more knee extension and a small amount of hip extension to begin displacing the barbell off the floor. I will explain later on what reaching knee-level is crucial in bit about the transition phase.

Common cues you probably have heard about this are:

- The angle of the body in relation to the ground remains the same from the start to the end of the first pull.

- The shoulders do not drop or shoulder blades lose their compact position.

- The hips should not "shoot" up too early, resulting in knee extension to occur first then hip extension (instead of more knee and little hip occurring at the same time).

The purpose of this phase is in fact to generate inertia to move the barbell off the ground and begin its acceleration. However, two common mistakes are to have inadequate tension in the trunk to properly utilise the leverages in the body to move the weight and to think moving the bar fast right from the start is going to generate good speed at the end.

Not maintaing the tension once the bar starts moving results in shifting the work to be done to either the upper back or even the arms to get the weight moving. Tension created in the start position and maintaining it will allow for the legs to be properly used and subsequently, the correct movement pattern of knee and hip extension to be executed.

Similarly, rushing this phase by yanking on the bar to get it to move is similar to Paul Walker (RIP) hitting the Noz button too quickly and subsequently not having enough top-end speed, only to see Vin Diesel fly past him. If you are going so fast in the first pull, when you need to accelerate the bar a second time, it ain't gonna happen. So this phase needs to be controlled with good speed and adequate tension in the body.

2. The Transition

Image from Rob Macklem.

Image from Rob Macklem.

This phase occurs between the position where the barbell reaches knee-level to the power position. This phase is the sequel to the first pull. If the end of the first pull is not executed correctly, you would already make two mistakes: 1) you would not get into the right position with the barbell at knee-level, 2) you would have rushed into the transition phase.

Before going further, here are the common cues for this phase:

- Barbell should remain in close proximity to the body or even be sliding up the thighs.

- Angle of the knee should remain the same as the knees are being pushed forward (due to the occurrence of the double knee bend)

- Torso needs to reach vertical and shoulders need to remain over the barbell for as long as possible and even slightly behind the barbell at the end of the phase.

In this phase, it is important to understand that your torso shifts the most in position (i.e. from an inclined angle to a vertical/close-to-vertical angle). This means that momentum created from the first pull has a greater tendecny to shift the combined centre of mass of the barbell and weightlifter in some form of horizontal direction and could result in losing vertical transfer of momentum.

One of the common mistakes is not getting the bar to the correct level at the end of the first pull. Too low and it would mean you have to either clip your knees or move the bar around the knees, resulting in unnecessary horizontal movement being started. Too high and your torso would already begin moving into a vertical position too early. Either of this would result in momentum of the barbell-weightlifter system to be moved in a slightly horizontal fashion.

Another mistake is the position of the torso. The transition is the phase where the torso angle changes the most (as mentioned earlier). Many would fail to understand that and remain leant over too much in the power position. This would mean that they have used their arms excessively to bring the bar into their hips and straight their legs out too much. On the other hand, there are also lifters who move the torso into an upright position too quickly. This would result in them either sitting back too much in the power position (or at the end of the transition phase) or cause momentum they have generated to keep moving behind the vertical reference line of the barbell. Both instances would affect the second pull and I will explain why later.

3. The Second Pull

The second pull is where the most force is developed. The second pull is where the barbell-weightlifter system has the most momentum in motion. The second pull is where accuracy, coordination and balance are critical. From the power position, force is developed through the extension of the whole body which gets transferred to the barbell to allow maximum displacement to occur. The second pull not only involves the legs but also the torso. Some agree it's a catapult effect that's occurring, some agree it's a triple-extension. How I was taught was that it was a kick/punch with the whole body, and no one body part or muscle group is solely responsible for the second pull.

In the second pull, common cues normally given by coaches are:

- Use the hips to drive the barbell in an upwards direction (not a forward direction).

- Keep the barbell close when executing the second pull.

- Fully extend the body and drive the feet into the ground.

One of the misguided cues I always hear is "when the arms bend, the power ends". Yes and no to some extent. Yes if other body segments and movements are taken into consideration when analysing the entire movement. For example, bending the arms to get the bar into the hips when the torso is leaning forward excessively results in a poor power position. Similarly, the power does end if the arms bend in the power position and straighten while the second pull is executed. This results in a loss of power or force transference to the barbell and sometimes in the barbell remaining in somewhat of a stationary position in the second pull.

Another mistake commonly seen in the second pull is the excessive desire to feel contact of the bar with the hips. Many coaches feel the need to ensure that there is the contact with the barbell, almost as much as a humping-action of the barbell with your hips. I mean I am fine with that only if there are two other actions involved with that: 1) along with that humping action, work is done to not only keep the bar moving close and vertical to the body and 2) shoulders or torso does not get thrown too much resulting in pulling the barbell too far backwards with an excessive backward lean of the body. The name of the game in the second pull is momentum (the product of mass and velocity). Keeping momentum in a vertical path in the second pull will allow correct placement of the barbell for the next phase of the lift.

4. The Turnover

Image by Rob Macklem.

Image by Rob Macklem.

The turnover is where all the work has been done to displace the barbell and require you to position yourself to receive the barbell. It is somewhat of an active phase still where you are trying to bring your body down as quickly as possible. In fact, it is a phase where timing has a role to play and determination is key to achieving a good receiving position.

Though not common to cue the turnover, here are a few that I have heard about the turnover phase:

- Guide the elbows out and up (and rotate them over as fast as possible for the clean)

- Move the feet out to increase the base of support

- Pull the hips down quickly into the bottom of a squat position (after opening it up in the second pull)

Personally, those cues I have mentioned are good. It is what the joints movements are for the turnover to occur. But as much as it is an active movement of those joints, it needs to be an instinctive movement. The mistake is that many think of how they should get into the receiving position. This results in the movement of the turnover becoming just that fraction too slow and result in the barbell already achieving a downward displacement while preparing for the catch position.

How I would normally cue for this phase is to ensure the athlete only thinks of (if he or she is doing any thinking) the catch position and nothing else. Moving fast into that position will require you to allow your motor control to take over and use whatever movement pattern you have in your body to achieve that catch position. Unless he or she is obviously bicep-curling the weight (for the clean) or keeping the arms stiff (in the snatch). Then exercises like your high hang drills or even just slowing down the first position of your high hang drills will help with learning to move fast under the bar.

5. The Recovery

This is the easiest of the 5 phases unless you either 1) have insufficient leg strength, or 2) rush through the catch position and cause instability in the barbell-weightlifter system. In the snatch, you basically perform the concentric portion of the overhead squat. In the clean, you peform the concentric portion in the front squat. Not being able to do this basically says that you do not have enough strength to firstly support the weight or you are in a poor position to move the weight, hence making the movement difficult. Once you have secured the catch position, the weight would be at a standstill which would then make it easier to stand it up.

Conclusion

That's my thoughts on the phases of the lifts. The phases of your lifts are what links the positions I previously mentioned in another article together. It is how you move from position to position that actually determines the outcome of the lift. Looking at position alone or phase movement alone is not going to help improve your lift overall. Being able to link all that together (the 5 key positions and 5 phases) is what's going to help put that heavy weight over your head.